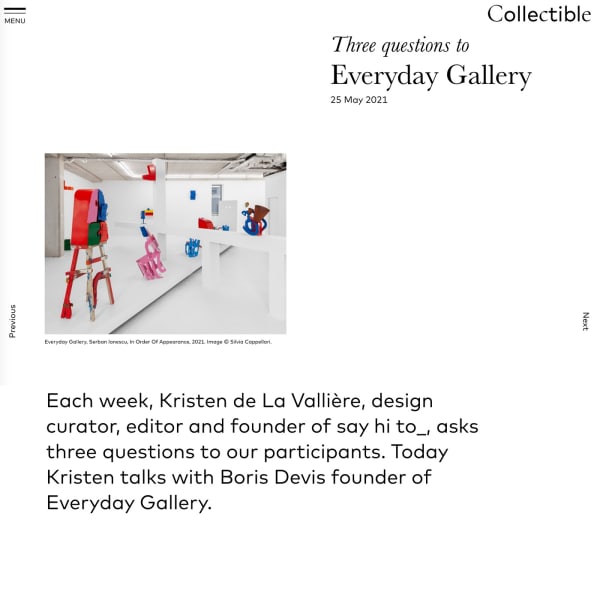

In Order Of Appearance: Solo Exhibition by Serban Ionescu

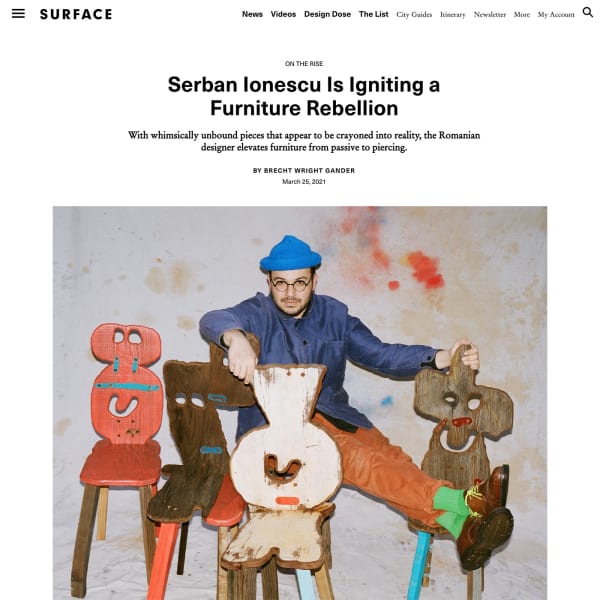

Born in Romania in 1984, Serban Ionescu was 10 when he migrated to the United States; old enough to vividly remember witnessing the assassination of Nicolae Ceaușescu on live television in December 1989, and young enough to playfully but wholeheartedly embrace American culture during his teenage years.

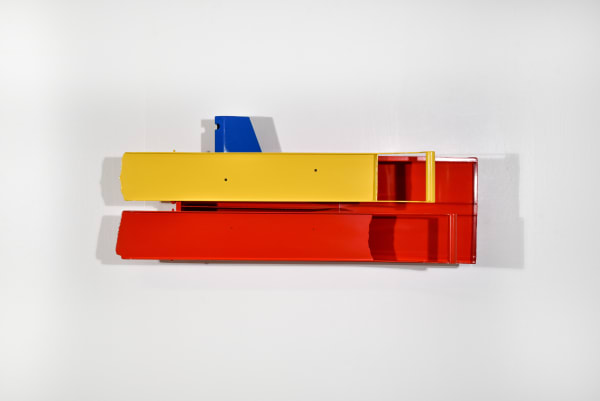

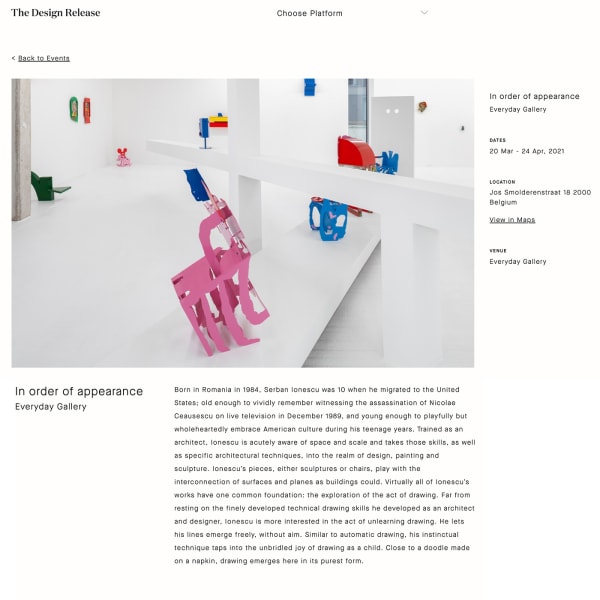

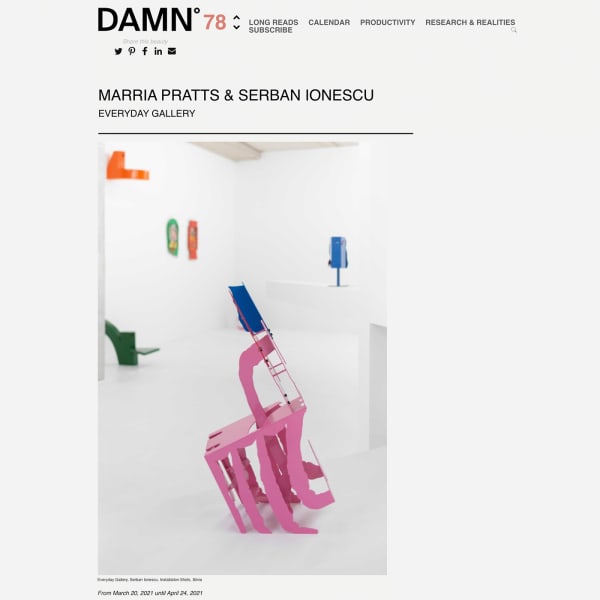

Trained as an architect, Ionescu is acutely aware of space and scale and takes those skills, as well as specific architectural techniques, into the realm of design, painting and sculpture. Ionescu’s pieces, either sculptures or chairs, play with the interconnection of surfaces and planes as buildings could.

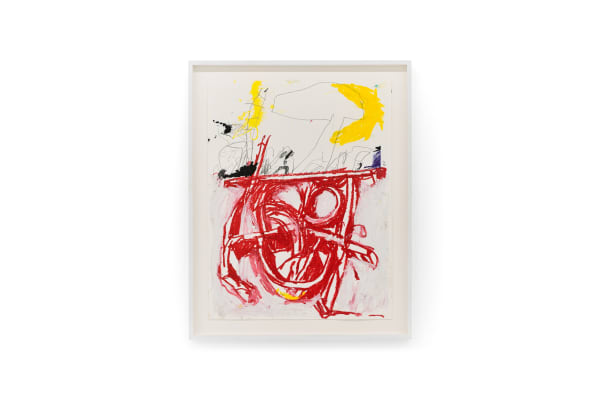

Virtually all of Ionescu’s works have one common foundation: the exploration of the act of drawing. Far from resting on the finely developed technical drawing skills he developed as an architect and designer, Ionescu is more interested in the act of unlearning drawing. He lets his lines emerge freely, without aim. Similar to automatic drawing, his instinctual technique taps into the unbridled joy of drawing as a child. Close to a doodle made on a napkin, drawing emerges here in its purest form.

These loosely drawn shapes without intent or purpose are then digitally processed, allowing the artist to experiment with shape, scale and color like only an architect would. We ultimately end up with the kind of sculptural works, designs and cut-outs that express Ionescu's unique aesthetic language.

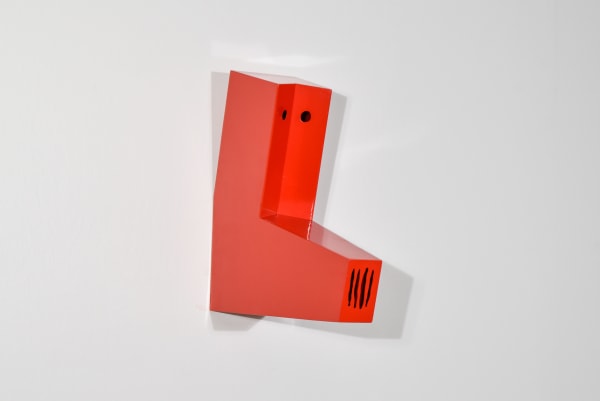

Amongst this varied body of work, Ionescu’s works conjuries up an almost cinematic reality, in which characters seem to emerge from piece to piece. Hence also the title of the show, In order of appearance. The title refers to the way actors tend to be credited in films, but also to the way that one moves through the exhibition. Progressing from piece to piece, the viewer slowly becomes aware of the story that brings all these pieces together and that turns these objects into characters. This cinematic quality is always present in the work of Ionescu; it forms the backdrop against which his works come to life.

This cinematic and dreamlike quality is also present in another way in Ionescu’s work. The childlike drawing technique that he employs may indicate carelessness, but in Ionescu’s case there is also an oblique reference to his own, dreamlike memories of living in the final days of communist Romania as a child. This is not so much about politics per se as it is about an atmosphere, a feeling, a memory. Thus, Ionescu connects carelessness and the dreamlike memories of political turmoil, childhood joy and childhood anxiety – all through the seemingly innocent act of doodling. Whether one sees things as careless or dangerous, Ionescu seems to say, is a matter of scale and perspective – the two things he likes to play with as an artist.

When confronted with Serban Ionescu’s work, one cannot help but feel transported on a set. Theater is the first association (not necessarily because another Ionesco of Rumanian origins was the world famous Eugène, author of surrealist plays such as “The Chairs”); yet it is certain that Serban could also easily adapt any of his visions for the cinema. Whether you consider his objects as furniture to be used daily, or as art pieces to be circumnavigated like sculptures, they are, before anything else, characters. They interact with each other like actors telling a story. “In Order of Appearance” is Serban Ionescu’s European première: a declaration of intentions.

Skilled in transforming raw materials - wood, cardboard, steel - with apparent insouciance, one has the feeling there is little premeditation in the way Serban assembles his objects. Also scale seems irrelevant, and what could fit a home, could just as well be several times larger and inhabit a square, an approach that has been clearly influenced by his architectural background. The aim, whatever the premise, is to bring personalities to the objects, infuse them with identity and expressions. It is not just the emoji transfer of smiles and frowns, but the subconscious exploration of the theme of masks. Are objects a way for us to hide or reveal ourselves?

Anthropomorphism is an innate tendency of the human psyche. It is also an ancient and well established mechanism of storytelling: it helps us make sense of a world which can be inscrutable and unpredictable. Attributing human traits, emotions or intentions to non-human entities, can be a strategy to cope with loneliness when other human connections are not available. Right now we could all do with a chair as a companion, an object with which we can have both an emotional, and a physical interaction.

Text by Bram Ieven

Images by Silvia Cappellari